I’ve been listening to WFMU, an eclectic radio station broadcast out of Jersey City, NJ, for many, many years. Two shows have been especially influential. The first, when I was in my early twenties, were broadcasts of Alan Watts lectures. The second is a one-hour gospel show that I’ve been listening to for more than 10 years. Kevin Nutt’s show, Sinner’s Crossroads, is partly responsible for one-quarter of A Life’s Work. Had Kevin’s show not exposed me to that music I wouldn’t have considered including Robert Darden and his work with the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project. (If you visit the Thank You 2009 page, the first year I gave thanks here, you’ll notice I thanked Kevin (and WFMU); that was long before I thought of interviewing anyone for the blog.)

Kevin writes: “My paying gig is as the folklife archivist for the Archive of Alabama Folk Culture in Montgomery. I also produce a weekly vintage gospel radio show on WFMU and when I have time I run the CaseQuarter label. I grew up in Montgomery and lived in NYC from 1990-1997 working in bookstores and attending Hunter College. I have one wife and two sons.”

And now, the interview.

I grew up in a Baptist church and my father was a Baptist minister. My mom loved music. She was the first person in her family who attended college and she majored in music. I was always fascinated by the songs we sang in church and pored over the hymns as we sang them especially noting the names of the composers and the publication dates. The Southern Baptist hymnal contains very few older, more formal hymns like Isaac Wyatts’ tunes. Most of them were written between the Civil War and World War 1 by American Protestants. Lots of Fanny Crosby’s, Showalter’s and the like: Standing on the Promises, Old Rugged Cross, Love Lifted Me. There was a certain distinctly American bounce to these tunes and hymns and except for the later Pentecostal hymn books most of these tunes were not even in Methodist hymnals. Since most of your black quartets were from Baptist churches there was a lot of hymn borrowing and later when I was a teenager and heard groups like the Soul Stirrers and the Swan Silvertones sing these very same hymns it just knocked me off my feet.

What are your duties as the Alabama Folklife Archivist and what are some of your biggest challenges as an archivist?

Right now, we are processing the 25 years of fieldwork collected by the folklorists who worked with the Alabama Center for Traditional Culture, the Alabama State Council on the Arts and the Alabama Folklife Association. Alabama has had an unusually strong public folklore presence and these folklorists collected an impressive body of recordings, photographs and the like documenting all manner of Alabama folklife. We are working off a big grant right now that’s allowed us to hire another archivist to help with the accession, processing and cataloging of the material. So I oversee that. My other duties include handling pretty much any kind of recorded sound material donations and requests that come our way and I also engineer and board op any of the various lectures and programs we have here at the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Right now, we are processing the 25 years of fieldwork collected by the folklorists who worked with the Alabama Center for Traditional Culture, the Alabama State Council on the Arts and the Alabama Folklife Association. Alabama has had an unusually strong public folklore presence and these folklorists collected an impressive body of recordings, photographs and the like documenting all manner of Alabama folklife. We are working off a big grant right now that’s allowed us to hire another archivist to help with the accession, processing and cataloging of the material. So I oversee that. My other duties include handling pretty much any kind of recorded sound material donations and requests that come our way and I also engineer and board op any of the various lectures and programs we have here at the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

The biggest challenge is coordinating, administrating and preparing much of these materials and collections to meet the needs of patrons in the digital world. People, rightly so, want access to collections digitally from remote sites. It’s a paradigm shift and archivists are wrestling with all kinds of practical problems digitizing collections and moving them to the digital domain.

There are many people with an interest in a certain genre of music. Some have so much enthusiasm for the genre, they become collectors, which I’m guessing you are. But archiving seems to be a whole other level of devotion. Was there a eureka moment that led you to pursuing that career?

Not really. I worked in bookstores in Alabama and New York, too, and it just seemed like a logical move to some kind of archiving work from there.

Is an archivist’s work ever done?

I hope not; that would mean humanity’s work would be done.

Do you think your DJ-ing and archiving are related somehow?

Why should an atheist in New York City care if gospel music is preserved or not?

For the same reasons that any other kind of spiritual or sacred music of any society or culture should be preserved. It is part of the expression of humanity. For many music aficionados in the US, listening to gospel music requires a type of leap of faith other music does not. There’s a (understandable) resistance to the music because certain types of gospel music are associated with reactionary political parties and views. At the same time black gospel religious music is more accepted among non-believers because it is associated with the black church and its participation in the Civil Rights movement. Gospel music has had such a huge impact, lyrically, melodically, musically, on American vernacular music as a whole. Clichés abound like “rock and roll began in the church.” I think there’s a lot of truth in that.

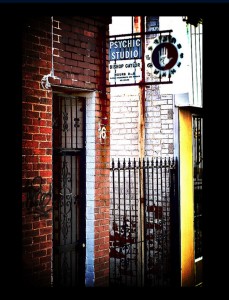

And this one is from mutual friend Christine Lofgren: Where do you find those great ads you play on Sinner’s Crossroads?

Sinner’s Crossroads has always been in part an homage to AM gospel radio stations in the South. There are so few left now, but as late as the 1990s one could hear these tiny, locally programmed stations everywhere. Many offered pay-as-you-go programming for anyone who felt the inspiration or call to get on the radio and preach, testify, rant or sing. It made for some spectacular radio moments. To this day, local spiritualists, hoodoo folk and psychic healers and readers’ best avenue to customers is on gospel radio stations. Even though there is often a great deal of tension between traditional denominations and the readers themselves, the gospel stations are how these folk get to their customers. So on these small, local radio stations you would hear between the gospel records and taped or live church service broadcasts these amazing self-produced commercials for local spiritualists and the like. In the 1980s, I started recording off the air a lot of AM gospel programming in Montgomery, Alabama. That’s where Sister ‘Leisha and Mother Marie and Reverend Izear Espie come from, those AM radio gospel stations. I don’t include them in my show as some kind of inappropriate or incongruent comic moment. Within the logic of these AM gospel radio programs they make perfect sense and indeed belong there.

Giant thanks to Kevin Nutt. Special thanks to Christine Lofgren for brokering the interview.

[color-box color=”gray”]What’s A Life’s Work about? It’s a documentary about people engaged in projects they won’t see completed in their lifetimes. You can find out more on this page.

We recently ran a crowdfunding campaign and raised enough to pay an animator and license half of the archival footage the film requires. We need just a bit more to pay for licensing the other half of the archival footage, sound mixing, color correction, E&O insurance and a bunch of smaller things. When that’s done, the film is done! It’s really very VERY close!

So here’s how you can help get this film out to the world. It’s very simple: click the button…

Donate Now!

… and enter the amount you want to contribute (as little as $5, as much as $50,000) and the other specifics. That’s it. No login or registration required. Your contribution does not line my pocket; because the film is fiscally sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts, all money given this way is overseen by them and is guaranteed to go toward the completion of this film. Being fiscally sponsored also means that your contribution is tax-deductible. So why not do it? The amount doesn’t matter as much as the fact that you’re helping to bring a work of art into the world. And that, I think, is really exciting!

Questions? Email me at d a v i d ( aT } b l o o d o r a n g e f i l m s {d o t] c o m[/color-box]