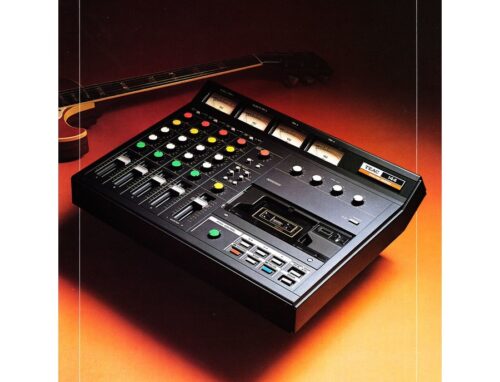

I recently read (well, listened to, actually) Deliver Me from Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, by Warren Zanes. (I recommend it.) A substantial part of the book delves into the technology Springsteen used to record the songs, a Teac 144 cassette deck. It was a notch above your off-the-shelf boom box, since you could record four-tracks on it, but it still recorded on a standard cassette tape, the kind you would buy at Radio Shack. Springsteen recorded the songs as demos–just him and a guitar, with the occasional harmonica–with the intention of bringing them to the E Street Band and turning them into “Springsteen Songs.” The demo was like a rough draft; some songs even seemed to end in the middle. It was sparse and raw and naked.

There is a lot to write about Nebraska and where Springsteen was in his personal life that he gave birth to these dark, dark, DARK songs. If you’re interested in that, read Deliver Me from Nowhere, or for the short version, watch this CBS This Morning video where Springsteen takes you into the room in which he recorded the songs and talks about how they came about. (In Springsteens autobiography, he spends about two pages on Nebraska.)

But I want to focus on the fact that the songs were captured on a cassette tape. Springsteen played the tunes for the band and tried to record a couple with them, but he didn’t care for the arrangements: despite all the layers of instruments, something was missing. He tried to re-record them solo in a professional studio, with the best microphones and an engineer and all the rest of it, but it still lacked the emotional power that came through on the crappy cassette. Then the decision was made–he would release the demo as is.

But there was a problem. No facility had the equipment to turn this cassette into a master from which commercial CD’s could be produced. The technology was obsolete, and whatever studio once had the ability to do it, scrapped their equipment probably ten years before.

+ + +

When we began shooting A Life’s Work, High Definition (HD) video cameras had just come out, but they were crazy expensive. Ancillary costs were a new computer with maximum processing power and RAM, and several of the largest external hard drives available at the time. And those, too, were expensive.

Shooting in Standard Definition (SD) was still viable in 2005. I had seen feature films shot on the Panasonic DVX 100 camera (the camera we wound up using) on a big screen and the upscaling looked great.

So I had some options:

Postpone shooting until the price of HD cameras and related things drop;Postpone shooting until I saved thousands of dollars more so I could buy the latest toys;- Shoot the film on Standard Definition and have it upscaled in post production;

Forget the whole project and concentrate on writing.

I chose door Number 3.

Somewhere around the fifth year of shooting, though, I began to worry. HD had come down in price as had hard drives and computers that could handle those files. I wondered if I should change over to HD. Would the difference between the HD footage and the SD footage be too jarring?

But I’m wary of changing formats, cameras, software, technologies midstream. (Sometime I’ll tell you about how poorly I handled the switch from Final Cut Pro on a Mac desktop–the OG “cheese grater” with an Apple processor–to Premiere Pro on an Apple Powerbook Pro with an Intel processor. This was 2009 or so, and since then Apple has resuscitated their cheese grater desktop and are making their own processors again.)

But the film gods looked upon me kindly. I realized the film was going to take a LOOOONG time to complete, and I could use a change from SD to HD to the film’s advantage.

And since we started shooting the film, the upscaling technology had also improved. My SD footage would never have the crispness and definition of HD footage, but converting the size, 640 x 480 footage to 1920 x 1080, had improved dramatically so that there was very little pixelation or aliasing.

Since the film is about the long view, it would make sense that the film showed how the changes that occurred in camera technology during those 15 years effected the look and style of the film.

And bonus, I love the soft look of the upscaled SD footage. It has a pastel quality, kind of old tymee, certainly relative to the hyper crispness of HD.

Finally there’s this, from the Epilogue of Deliver Me From Nowhere.

It [Nebraska] reminds me, and I’m sure many others, that we shouldn’t wait. The important thing is that you make it and mean it. If you have those two things covered, how good it sounds will matter far less. Because the whole “how good it sounds part” is not what people are listening for when they really need a song.

Amen to that.