In December 2013 the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture announced that it would be welcoming into its collections recordings from the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project, yes, the project started up by Robert Darden and featured in A Life’s Work. Big news. I asked Robert if he’d share how this came to pass. Ever the gentleman, he agreed to a mini interview.

Kathy Wright, then a Baylor development officer (now a regent), encountered former First Lady Laura Bush in Washington D.C. and, in the course of the conversation, told her about the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project (BGMRP). Mrs. Bush, who is on the board of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), currently in progress on the Mall in Washington D.C., was intrigued with our work and shared the information with someone at the NMAAHC. They contacted us in Fall 2011 and invited us out to speak with them. Tim Logan (VP for IT at Baylor) and I flew to D.C. and made a presentation. Apparently, they liked what they heard.

Kathy Wright, then a Baylor development officer (now a regent), encountered former First Lady Laura Bush in Washington D.C. and, in the course of the conversation, told her about the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project (BGMRP). Mrs. Bush, who is on the board of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), currently in progress on the Mall in Washington D.C., was intrigued with our work and shared the information with someone at the NMAAHC. They contacted us in Fall 2011 and invited us out to speak with them. Tim Logan (VP for IT at Baylor) and I flew to D.C. and made a presentation. Apparently, they liked what they heard.

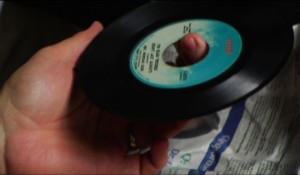

For the NMAAHC, this means they have immediate access to the largest digitized collection of rare black gospel vinyl in the country. How they are going to use that access is still a work in progress. At one point, the NMAAHC was planning to move an intact African American record shop from Philadelphia into the building. Visitors would have the total experience, complete with thousands of soul, R&B, blues, and gospel LPs and 45s. Somehow, there will be a link on the vinyl that will allow visitors to listen to the music, perhaps through their cellphones, perhaps through headphones. All of that is still being decided.

From the BGMRP, nothing changes. We will continue our quest to locate, identify, acquire (through loan or donation), clean, catalogue, and digitize America’s fast-vanishing legacy of gospel vinyl from the 1940s through the 1960s.

Our biggest challenge now is how to make that music more widely available, though the constraints of modern copyright law. It is currently available for scholars, but the general public can only hear 30 seconds of each song, save for those individual songs we’ve cleared through copyright control and have made available for free on iTunesU.

Will your role change?

For me, nothing changes. I’ll still teach at Baylor. I’ll still work on Nothing But Love in God’s Water: The Influence of Black Sacred Music on the Civil Rights Movement, Volume II for Penn State University (Vol. I should come out in mid- to late 2014). The connection with the NMAAHC gives us wider visibility and, hopefully, more access to their experts. I will continue to be the “face” of the BGMRP. For the future, I would love to explore with them the options of making this music even more available, perhaps through the Smithsonian’s Folkways Records.

For gospel music and the public at large, this partnership is another step in insuring that this irreplaceable musical and historical treasure is preserved for all time. This is the foundational music of all American popular music. Every step, hell — every piece of vinyl — is important, perhaps essential to understanding not only the history of music in America, but the history of African Americans.

First, I didn’t believe that the by-God The New York Times would actually RUN my little rant. They receive hundreds of submissions a week. I had no expectations, no plans. I was angry and hurt and wanted to vent in the biggest forum in the world. If I had any secret wishes, I don’t remember them … although I may have hoped that somehow some record industry exec would read it, be shamed, and release some of the music they’ve got stockpiled.

So, no. I wouldn’t have believed any of this would have happened.

When the OpEd actually was published, I couldn’t believe that one of the first calls was from the office of Mr. Charles Royce, who wanted to brainstorm on HOW we could save this music. I was in a daze all day.

I’d like to stay involved with the BGMRP as long as I am physically able. I would like to help insure that every part of the operation is fully funded and endowed so that it is protected from anything that might (God forbid) happen at the university.

We are just starting to acquire the sermon tapes of some of the most famous African American preachers in the country. I would like to save as many of those as possible, particularly those active during the Civil Rights Movement. Most are on cassette tape, which is the absolute worst for preservation purposes.

Finally, my big dream is to raise money for an 18-wheeler with a mobile recording studio (and image-scanning devices) that we could take both the warehouses of the big collectors who have said we could digitize their materials (but that they won’t allow them to be mailed) and to the parking lots of the great African American churches in Chicago and Birmingham and open them up to the public. I’d say, “If there is black gospel vinyl in your attic, let us digitize it RIGHT HERE AND RIGHT NOW. We’ll give it back to you AND give you a CD or MP3 of it. If you’ve got photos of grandma posing at church with Sam Cooke or Dorothy Love Coates, we’ll scan and digitize it RIGHT HERE AND RIGHT NOW and give you the original and a scan back!”

Thanks, Bob!

Here’s a clip from A Life’s Work of Bob explaining why so much of this music is missing.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VxtEO1JGWoQ&list=PL851B3C5054DEB92F&index=3[/youtube]