When I was at the MacDowell Colony in 2010, I met a fine photographer, Matthew Connors. When I told him about the people in A Life’s Work, he asked if I knew the work one of his colleagues at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Barbara Bosworth. I didn’t. But Bosworth had been to MacDowell, and her book of photographs, Trees: National Champions (MIT Press; Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 2005) was in their library. I checked it out and was blown away by its beauty. I wished I had had this book as a reference before I shot a single tree for A Life’s Work. It only took three years, but I finally asked Connors to introduce me to Bosworth. She responded to my request for an interview enthusiastically, and agreed to share some photographs that do not appear in the book. It is my great great pleasure to share with you her words and images.

+ + +

Where did the idea for a book about trees come from?

I grew up surrounded by a forest. My “playground.” I have always loved being around trees.

I learned of the National Register of Big Trees in 1990 and immediately set out to photograph the trees on the list. After 14 years, a book felt right.

What’s the most difficult thing about photographing trees? The most enjoyable thing?

The most difficult aspect: getting to the trees.

The most enjoyable aspect: getting to the trees.

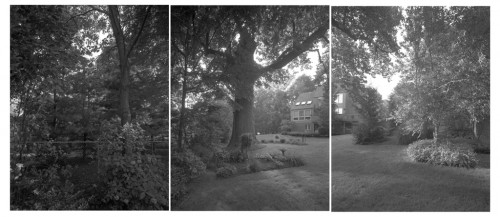

Many of the photographs suggest the presence of people — a bike, a telephone pole, buildings, fences (there seem to be a lot of fences around champion trees), but there are very few people in them. Why?

To me, this work is as much about the American landscape as about trees. These trees are in our backyards, along our highways, next to parking lots. The human presence is important in telling the story of the American landscape. I am interested in that presence.

In addition, including recognizable human artifacts in the scene provides a sense of scale. We can read the size of the tree by its proximity to a car, or a bicycle or a fence.

Can you tell me about why you made some of the artistic choices you did (black-and-white, the use of triptych and diptych, horizontal instead of vertical orientation)?

In a black-and-white photograph the world is pared down to forms in tones of grey, not distracted by that red sign or blue house or orange fence. I wanted these photographs to simply be about the tree and its environs. At times, in a color photograph, a red sign takes on greater importance than a brown tree. In these photographs, I want us to be aware of the sign, the house and the fence, but not to let the colors dictate their importance in the scene.

Plus, I like black-and-white photography’s reference to history.

I use multi-panel images as a way to show how the tree is in its surrounding landscape. It’s not just about the tree. It’s everything around it, as well.

While these photographs are of the largest tree of each species, this work, for me, has never been about size. Not all these “champions” are large. A champion Pussy willow is not the same size as a champion Red oak.

By choosing to photograph a vertical subject in a horizontal format, it keeps the emphasis on the landscape.

There are 70 plates in the book. I wonder how many photos you actually took and what the editing process was like?

The 70 images in the book are edited from several hundred. Many friends helped me with the editing and sequencing. MIT Press was wonderful to work with. Their insight and guidance was instrumental in shaping the book.

And, because the trees are ever changing, I continue to photograph these trees.

+ + +

Barbara Bosworth is a photographer whose large-format images explore both overt and subtle relationships between humans and the rest of the natural world. Whether chronicling the efforts of hunters or bird banders or evoking the seasonal changes that transform mountains and meadows, Bosworth’s caring attention to the world around her results in images that similarly inspire viewers to look closely.

Bosworth’s work has been widely exhibited, notably in recent retrospectives at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona. Her publications include Trees: National Champions (MIT Press; Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, 2005) and Chasing the Light (Nightwood Press, 2002).

I’ve conducted many interviews for this blog and elsewhere. See the entire list here.

[color-box color=”gray”]What’s A Life’s Work about? It’s a documentary about people engaged in projects they won’t see completed in their lifetimes. You can find out more on this page.

We recently ran a crowdfunding campaign and raised enough to pay an animator and license half of the archival footage the film requires. We need just a bit more to pay for licensing the other half of the archival footage, sound mixing, color correction, E&O insurance and a bunch of smaller things. When that’s done, the film is done! It’s really very VERY close!

So here’s how you can help get this film out to the world. It’s very simple: click the button…

Donate Now!

… and enter the amount you want to contribute (as little as $5, as much as $50,000) and the other specifics. That’s it. No login or registration required. Your contribution does not line my pocket; because the film is fiscally sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts, all money given this way is overseen by them and is guaranteed to go toward the completion of this film. Being fiscally sponsored also means that your contribution is tax-deductible. So why not do it? The amount doesn’t matter as much as the fact that you’re helping to bring a work of art into the world. And that, I think, is really exciting!

Questions? Email me at d a v i d ( aT } b l o o d o r a n g e f i l m s {d o t] c o m[/color-box]