I recently watched “The Making of Touch the Sound,” one of the extras on Thomas Riedelsheimer’s film about percussionist Evelyn Glennie. In it Riedelsheimer reveals that he envisioned the staged improvisational musical segments between Glennie and composer Fred Frith to be the spine of the film. The director planned on showing them footage of the film with the idea that the musicians would then improvise based on those images. But the musicians balked.

Frith tells the filmmaker, “I think the danger is when you give an idea which has got too much information and therefore whatever we do tends to become descriptive and I think descriptive music is not good. It fails. It doesn’t describe anything.”

Cut to the director addressing the camera–

“My idea was to give them ideas to which they could improvise. At the time I didn’t know that this is a contradiction in terms, as improvising requires the liberation from any conception or idea.”

And so Glennie and Frith let the space, the moment, and each other inspire them, not the footage. Riedelsheimer was clearly not pleased. At the time, he saw what he imagined as the entire structure of his film fall apart.

This struck a chord. Before filming began, I had many ideas about what A Life’s Work was going to be and not going to be. I am sticking with many of these ideas, but I have jettisoned just as many if not more. Some because they were impractial, some because they were incompatible, and some because they were just stinker ideas.

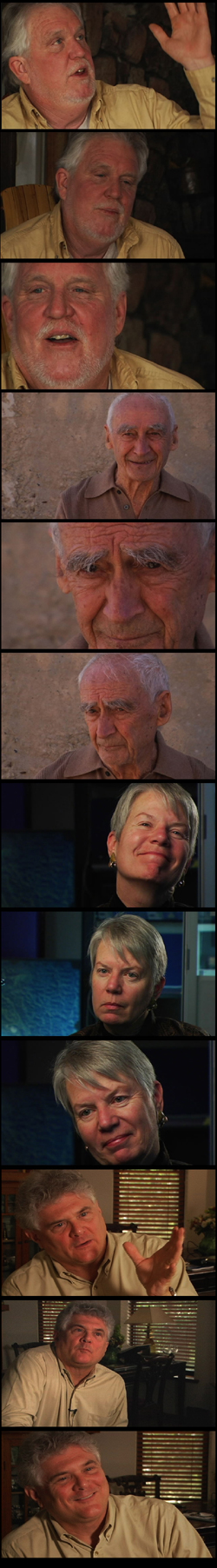

For instance: No talking heads. I was going to use just the subject’s voices over images of their work and images of them working. Talking heads, I convinced myself, were a crutch. I carried this idea to an extreme and conducted my first interview with Arcosanti architect Paolo Soleri audio only. Not surprisingly, this did not please Wolfgang Held, the cinematographer. We had an animated discussion about it the day of the first interview and I won that battle. But the next day I realized what a crap idea that was for this film and so we interviewed Soleri in front of the camera.

Look at these faces. I can’t believe I thought my audio only idea was a good one. And the thing is, I love the human face and find it a fascinating subject to photograph. There is no living thing on the planet more expressive. Since that interview, I conduct all interviews in front of the camera. So, what was I thinking? In my defense I can only say that I have a tendency to be reactionary. And you know, the idea isn’t always a terrible one. It worked brilliantly in Al Reinert’s For All Mankind, a wonderful documentary composed of NASA Apollo footage and audio only interviews with Apollo astronauts. But Reinert’s film is a special case and that approach wouldn’t work for A Life’s Work.

Thankfully, I was saved from this idea very quickly. I’m awfully glad I have people around me who will call me on stuff, because in the end, it’s not about implementing all of my ideas, it’s about what works best for the film.